The latest buzzwords in high-performance home theater include terms like “Immersive Sound” and “3D Sound.” What do these terms mean, and where do they originate from?

A little history: channels

Until recently, all sound recordings were “channel-based.”

Mono recordings used a single channel, regardless of how many speakers might be employed – think of a public address system, for example.

Stereo recordings use two distinct channels and (usually) two speakers. The magic happens when you sit with them equally spaced in front of you, and music appears to come from the space in between. On superb systems, you aren’t aware of the speakers as sources of sound at all. Sonically, they disappear, and you hear a detailed wall of sound coming from that end of the room.

The trick here is that if you place a copy of the same signal into two channels, and everything is just so, our ear/brain mechanism perceives the sound as coming from between the two speakers.

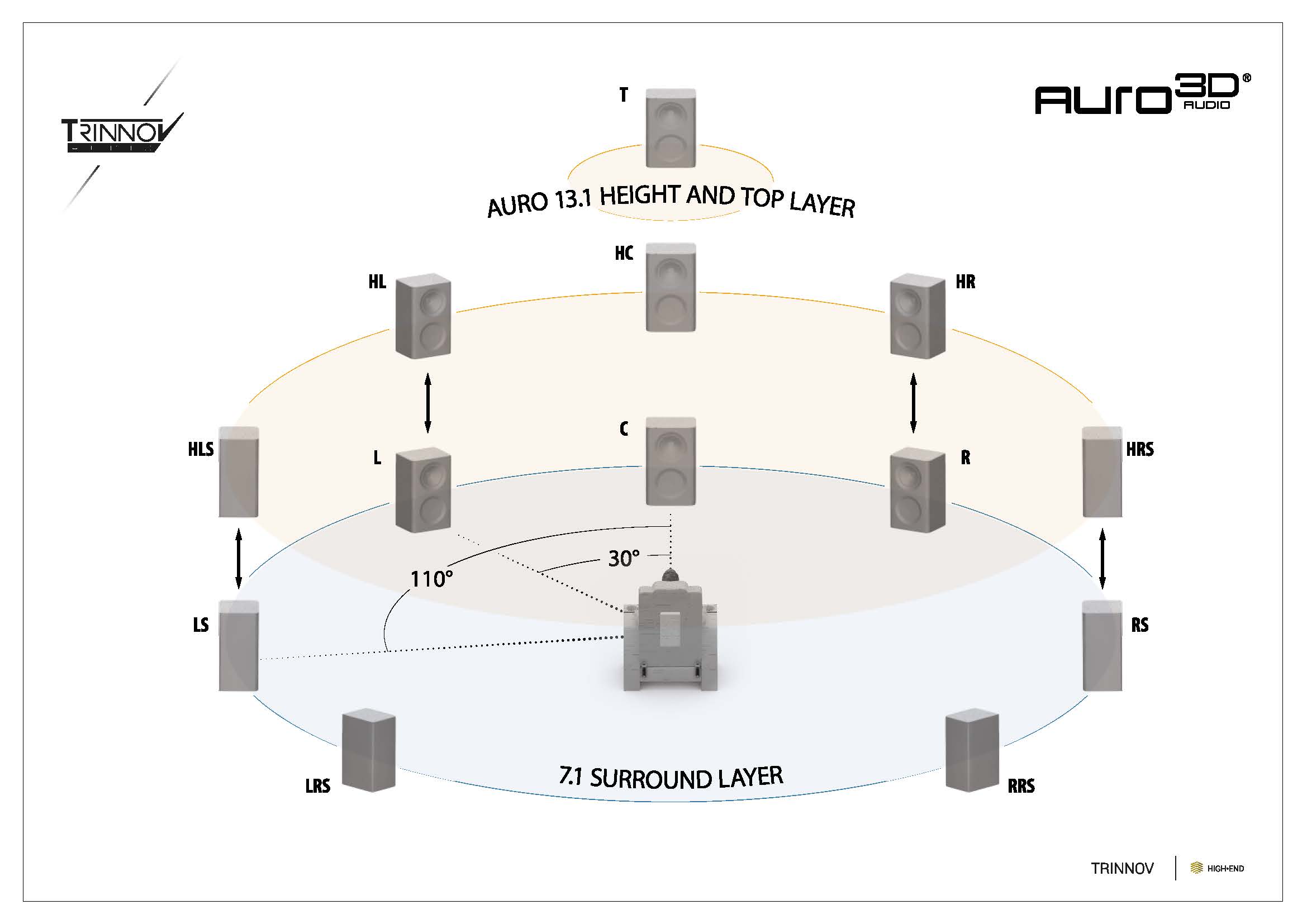

AURO-3D includes two distinct levels of height channels for maximum immersion.

Surround sound systems vs stereo

Frank Sinatra was famous for insisting that he be placed dead-center in any stereo recording he made. That is, Frank’s voice was mono and duplicated in both channels, even though other musicians might be mostly on one side or the other. That made him front-and-center in the recording and ensured that even people sitting much closer to one speaker than the other would still hear him. (You didn’t mess with Frank.)

More recently, “surround sound” systems commonly provided as many as six or eight such channels, one of which was often referred to as a “dot one” channel to denote that it was only for the deep bass, not for a full-range signal. Hence “5.1” and “7.1” movie soundtracks where you have sound all around you in the horizontal plane plus a dedicated channel for dynamic, deep bass.

Typically, these surround sound systems boiled down to:

- three speakers in front (Left, Center, Right) plus

- either two or four "surround" channels to your sides and/or behind you, plus

- the Low Frequency Effects (LFE) channel used by sound designers when they wanted to shake you up, as with explosions or threatening, deep bass in the musical score

Of course, mixing with these extra channels beyond simple stereo is a bit more complicated. But the principle is the same: if you want something to appear between two presumed speaker locations, you put some of that particular sound into both of those adjacent speakers… just like Frank.

Fairland Dolby Atmos Dubbing Stage (Germany) featuring the Altitude32

Defining immersive sound

What was lacking, however, was the critical third dimension of height.

After all, we live in a three-dimensional world. An added layer of realism can be accessed when we can hear things both above and around us. It might be a dramatic flyover or the atmospherics of birds flying and insects buzzing around in the jungle. But, when used intelligently, it makes everything more real and more engaging.

Having more speakers throughout the room improves the potential, perceived spatial resolution. But, when you add more speakers, creating content becomes more complicated. Not to mention another problem: what if some people don’t have all the speakers you might have imagined that they would have? Do they simply miss out on essential sounds in the mix?

Introducing immersive audio “objects”

The answer: what if we take an entirely new approach that takes advantage of the incredible processing power we have today in computers and DSP chips?

All channel-based systems assume a specific arrangement of speakers and then leave it to the mixer to figure out which ones should be used to make a sound “appear” in a certain place. What if we change the approach?

How about attaching a simple description to each sound, describing where it is at any moment in time? This “metadata” (which simply means “data about other data”) could be updated regularly, perhaps in every frame of a movie, for example.

By changing the location metadata over time, we can make objects move. If we include all three dimensions (length, width, and height locations), we could make any sound or collection of sounds move around in the room in any way we wished.

Both Dolby Atmos and DTS:X Pro use metadata to describe sounds’ locations within the room.

Ford vs Ferrari

Metadata to the rescue

Think about this: imagine the sound of a race car speeding around a track. You can see the car approaching in the distance, off on the right side of the screen. As it gets closer, it gets louder and zooms across the screen from right to left, with the resulting Doppler shift of the sound as it goes past you. It screams off the left edge of the screen and continues down the left wall until it disappears into the distance behind you.

A sound designer could, in theory, pan this sound carefully from the Right speaker, through the Center speaker, to the Left speaker, and on down to the Left side surround and the Left rear surround before it faded out entirely. That would be the channel-based way of thinking about the task at hand.

Alternatively, the same designer could associate the sound of that race car with locations (coordinates) that move smoothly across the front of the room and then down the left side of the room. It is the same sound, but now with metadata telling the playback system where it should be from one moment to the next.

What is the advantage of doing it the second way, with metadata?

The second, object-oriented way, is scalable. It doesn’t care how many speakers you have in your room because it is not referencing a specific speaker – just relative locations. Importantly, these locations can include the space above you and around you, enclosing you in a “bubble” of sound.

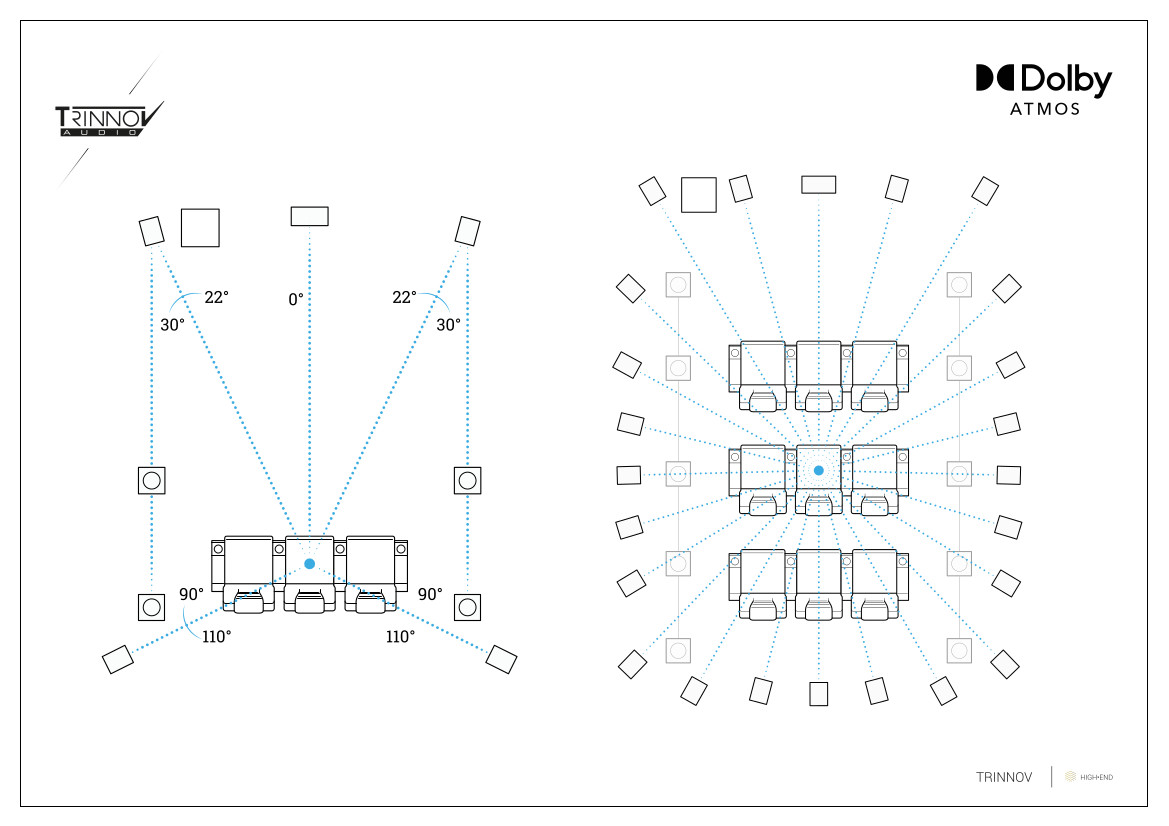

It is the job of a $400 AV receiver or a $40,000 AV preamp to “render” these movements (to the best of their abilities) among the various speakers it knows it has available. That could be a basic 5.1.4 system or a much more sophisticated system with vastly higher spatial resolution of sounds moving around the room:

Dolby Atmos supports various speaker layouts from the basic 7.1.4 to the most complex ones !

Creating immersive audio

From a practical, sound designer’s perspective, object-oriented tools like Dolby Atmos provide a wealth of creative options. For example, watch just one minute of the following documentary on the making of Ford vs. Ferrari

Producing immersive soundtracks

The little yellow balls on the Dolby monitor indicate where different sound objects are and how they move over time.

Of course, not all sound engineers use the tools in the same way. Dolby and DTS created these powerful tools to expand the creators’ artistic possibilities and the audience’s resulting engagement. But there is no Dolby or DTS police force out there making sure that the tools are used as intended.

Sadly, producing immersive soundtracks takes more time and therefore costs more money. . A cost-effective shortcut exists, though. It consists of simply creating some objects up on the ceiling, never moving them, and then mixing as though those objects were simply additional channels. The resulting mix has become known as a “preprint” since it is almost as though they had “pre-rendered” the Atmos or DTS:X bitstream for the AV receiver or preamp.

There is nothing that the surround sound decoder can do without usable metadata– no matter how sophisticated it might be. The requisite information simply isn’t there.

Dolby Atmos Viewer

Fortunately, consumers have pushed back – especially the movie enthusiasts who, though smaller in number, consume many more movies than the general public. Even the most egregious studios are getting the message and are investing more time and effort in their immersive audio soundtracks.

On the Trinnov Altitude, you can see how the sound designers constructed the soundtrack with our Dolby Atmos Object Viewer. This unique display shows how the objects’ movements influence the speakers’ volume as they move by. The most simplified sound designs and mixes are exposed because their audio objects rarely, if ever, move.

On the other hand, you can easily see and hear the result of those creative sound designers who embrace the power of the new tools. (This is an example of one of many features only available on the Trinnov Altitude platform.)

The beauty of Object-Based Audio

Moviemakers have a considerable challenge: they have zero control over how the consumer experiences their art.

Is it on the two itty-bitty speakers built into a flat-panel TV? On a “home theater in a box” bought at a big box store? Or in a dedicated home theater such as they might own themselves? Or perhaps even better?

They have no way of knowing, yet their movie must always entertain… or else they may not be making another one in the future.

Arri Atmos mixing stage featuring Trinnov MC Processor

Conclusion

Object-based audio like Dolby Atmos or DTS:X provides a way of building in a tremendous amount of artistic freedom and the potential for truly immersive experiences on a good system. Such technologies allow you to truly escape into a good movie while at the same time guaranteeing “backward compatibility” with the most basic TV systems people use today. It is one soundtrack with almost unlimited ways of being rendered to the available sound system.

How many systems do you want? It’s entirely up to you. Using these technologies, the same movie on the same disc or streaming platform can take full advantage of whatever system you have available. Even better: if you improve your system, you can go back to a favorite movie and hear it all over again, complete with all the benefits of your improvements.

We are all staying at home more these days. Do you feel the need to escape once in a while? While nothing will replace being able to get together with friends and family again, having an immersive sound system in your home can be the Great Escape you need in the here and now. It will also be a fantastic thing to share with your friends and family when that time comes around once again.

Please see our Technical Blog for more ideas.